Bertrand Lavier Morceaux Choisis

In Morceaux Choisis, Bertrand Lavier’s latest exhibition with the gallery, the artist unveils two new bodies of work, alongside extensions of his ongoing chantiers or ‘worksites’. The exhibition title — French for ‘selected pieces,’ or ‘anthology’ — sets the tone, invoking notions of choice, arrangement, and display that lie at the centre of Lavier’s practice. It also speaks to the breadth and variety that define his work, making it an especially apt name for these new bodies of work.

The exhibition opens with a metaphorical bang: the wreckage of a Fiat 500, one of the icons of the last century’s golden era of the automobile, its crushed body painted in a glossy, enticing red. Standing in isolation at the end of the gallery, on a platform that functions more like a stage than a plinth, Fiat 500 is the latest of Lavier’s damaged car works, the origins of which can be traced back to his seminal Giulietta (1993). Emblematic of the irony, humour and semantic play that characterise Lavier’s practice, Fiat 500 introduces some of the exhibition’s central concerns: the boundary between art and the everyday; between representation and reality; between language and meaning; and the status of the object in relation to authorship.

Unlike the American artists associated with cars, such as Warhol or Charles Ray, Lavier neither aestheticises disaster nor fabricates it. He selects a wrecked vehicle and presents it as a fait accompli: the damage is not produced but ‘found’. Its destruction generates a new form, showing how a sculpture can exist without being ‘made’ in any conventional sense. Part Duchampian ready-made, part painted object, Fiat 500 becomes a hybrid artefact that short-circuits perception: is it sculpture, painting, or both? The dissonance between model and paint colour further sharpens the work’s conceptual edge: this is not simply red, but Lamborghini red — a reminder that naming itself produces meaning. Stripped of function and steeped in design and brand mythology, the car is reborn as a singular ruin — seductive and disturbing, pristine and damaged, an object of both desire and disquiet.

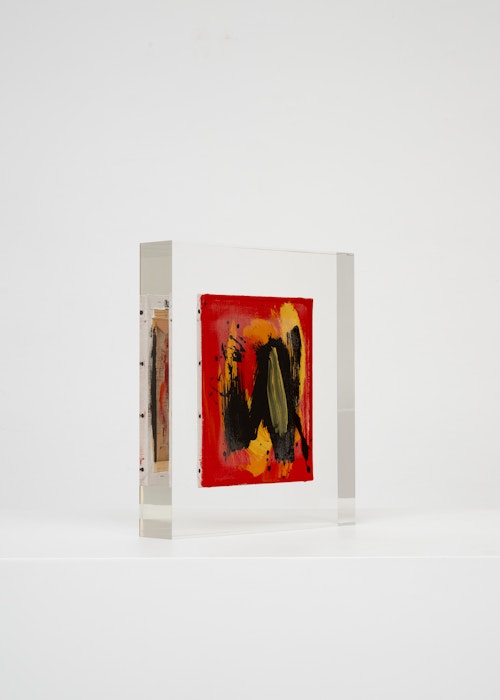

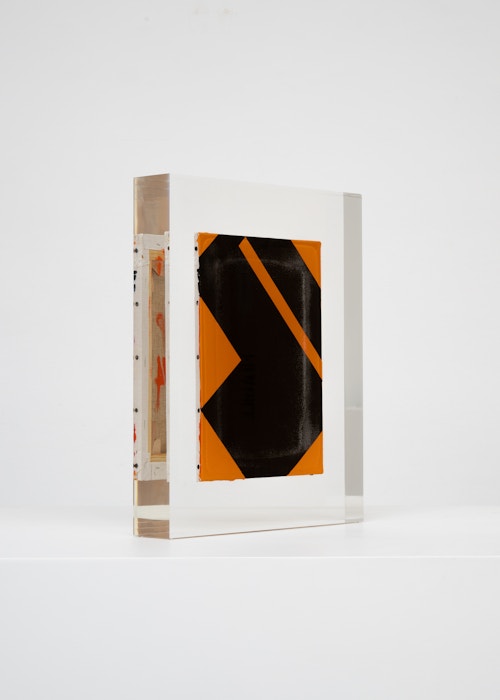

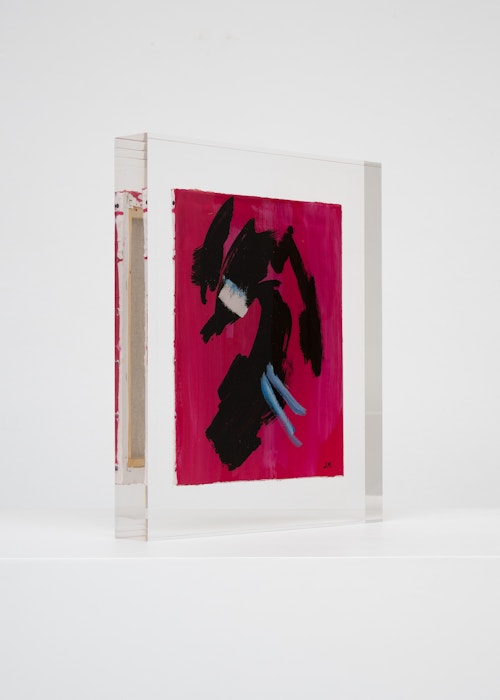

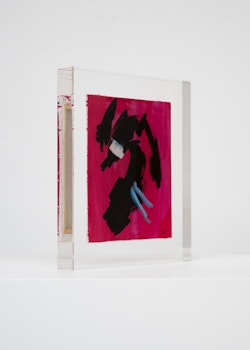

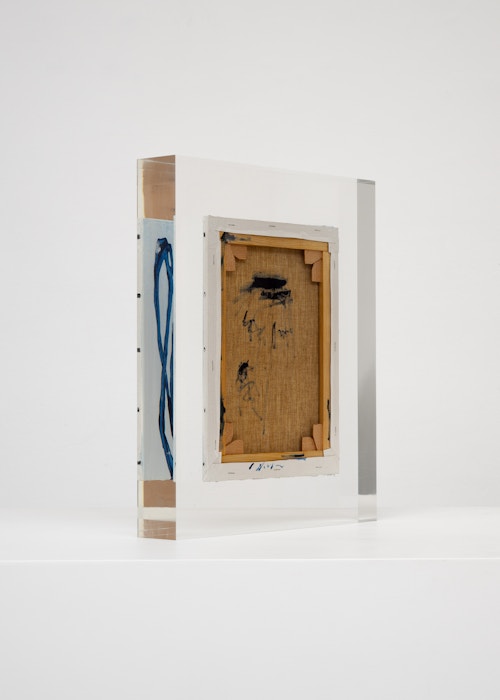

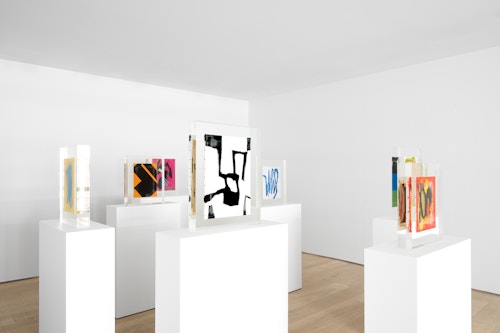

Upstairs, Lavier introduces a new body of work: Inclusions. These abstract canvases — found in flea markets and junk shops — are encased in blocks of acrylic resin. As with the wrecked Fiat 500, these works are ‘found’ rather than made: Lavier’s intervention is conceptual, grounded in selection and display rather than painterly authorship. Encapsulation produces another kind of perceptual short circuit. While the gesture recalls the New Realists, especially Arman, here it probes a modernist taboo: the separation of painting from sculpture. With both the front and back of each canvas visible, traditional viewing hierarchies dissolve. These once-anonymous paintings are suspended between states: object and sculpture, discarded and elevated, protected and entombed. Arranged as what Lavier calls an ‘abstract bouquet’, the seven works playfully challenge orientation and display, to quote Lavier, ‘the reverse side becoming more interesting than the front’. At the same time, the paintings selected for the Inclusions are diverse enough that they resemble a group show — an idea that harks back to, and expands upon, Lavier’s previous exhibition at the gallery, Walt Disney Productions (2016), where he explored abstract painting and its representation in popular culture.

Shown in the same gallery, Brushstrokes forms the exhibition’s second new body of work. Fabricated from painted steel, these literal brushstrokes translate gesture into three-dimensional form, occupying a similarly ambiguous territory between painting and sculpture. Unlike the Inclusions, which rest on plinths and invite the viewer to move around them, the Brushstrokes are wall-mounted, like paintings — yet they do not lie flat. In contrast to figures such as Roy Lichtenstein, who depicted brushstrokes, Lavier gives them physical presence. The difference signals a broader divergence between American Pop Art’s interest in representation and the European tradition of New Realists’ commitment to presenting reality itself.

In the adjacent gallery, Lavier presents four new paintings from a selection of his most renowned chantiers: a painted vitrine (based on Parisian shop windows), a painted mirror, a painted Fujichrome, and a juxtaposed colour painting. In the vitrine, Lavier transforms a utilitarian surface into an ambiguous pictorial field. Starting from a photograph of a blanked-out shop window (in this case, from Rue Elzevir, which is named after the seventeenth-century Dutch publishing dynasty), he digitally transfers it onto canvas, collapsing distinctions between transparency and surface, display and depiction. A site of commerce becomes a stage for painterly gesture, raising questions about what separates images from objects and art from display. Two layers of anonymity coexist: the unknown painter who obscured the vitrine and the technician who printed the image. Lavier himself is both absent (his hand is not visible) and present (the work exists through his orchestration).

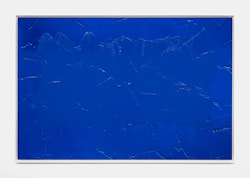

The painted mirror operates on a similar threshold. Here, painting disrupts reflection, preventing the viewer from accessing their own image. The mirror ceases to function as a tool of self-recognition and becomes a paradoxical object — one that reflects painting rather than the viewer. In Bleu de Cobalt (2025), the painted Fujichrome, Lavier again intervenes in the logic of photographic reproduction: painting tone-on-tone onto a print of a blue surface, he introduces the hand into a medium associated with mechanical precision. The result is a hybrid surface in which photography’s promise of objectivity is destabilised by painterly subjectivity, blurring the divide between lens-based image and painted gesture.

Finally, the juxtaposed-colour painting Bleu de France par Tollens et Ripolin (2025) addresses painting in its most elemental terms. Here, Lavier explores colour not for its representational potential, but as pure matter. In doing so, these works assert painting as a physical and material presence rather than a representational system, shifting attention from depiction to an immediate encounter with colour itself.

Bertrand Lavier (b. 1949, Châtillon-sur-Seine, France) lives and works in Paris. In 2012, he had a major retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, Paris. Recent solo exhibitions include Bertrand Lavier, Fosun Foundation, Shanghai & Chengdu, China (2022-2023); Unwittingly but Willingly, Le Consortium, Dijon, France (2021-2022); Bertrand Lavier, Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection, Paris, France (2021); Medley, Espace Louis Vuitton Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan (2018); Walt Disney Productions, Kunstmuseum Luzern, Lucerne, Switzerland (2017); Oeuvres in situ / Anémochories, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France (2016).