Running alongside the physical exhibition As you wish, this online exhibition Bist du bei mir examines the intersection of life and work for choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and visual artist Steven Fillet. Both exhibition titles hint at Johann Sebastian Bach’s Goldberg Variations, which not only provides the overarching framework for this project but also reflects the rhythms, structures, and sensibilities through which life and work are intertwined for both artists.

Just as the exhibition title As you wish hints at the Quodlibet, the name of Bach’s final variation, the online exhibition Bist du bei mir takes its title from the aria “Bist du bei mir, geh ich mit Freuden zum Sterben und zu meiner Ruh,” preserved in one of the two notebooks Bach compiled for his wife Anna Magdalena. Notably, in these notebooks, Bist du bei mir appears directly before the aria that opens onto the labyrinth of the Goldberg Variations. Its presence in the notebook led to the long-held assumption that Bach composed it.

Echoing the sense of companionship suggested by this musical context, this online exhibition reveals how the place where De Keersmaeker and Fillet live, with grazing horses and cultivated land, becomes their studio. And how the rhythms of daily life and the cycles of nature flow through their artistic practices. In times of fragmentation and withdrawal, this being-together operates as a quiet resistance. Here, works by De Keersmaeker and Fillet are placed in close proximity, allowing an open, lively dialogue to unfold— “a double helix,” as De Keersmaeker once described it, “oppositional strands advancing and receding, interlacing into a figure eight that holds the promise of infinity.”

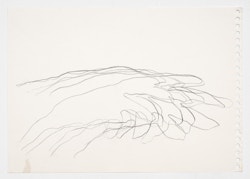

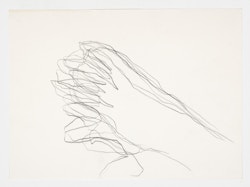

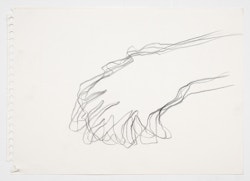

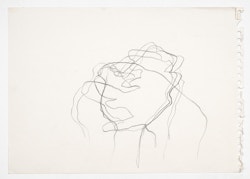

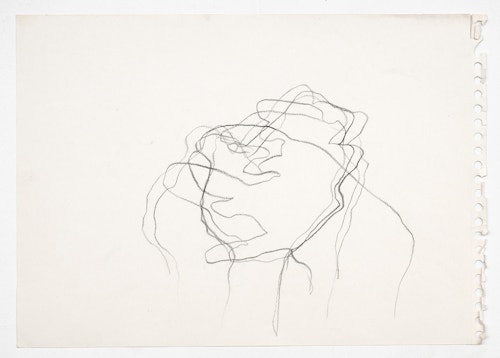

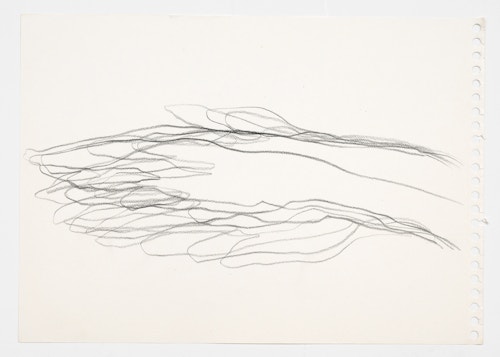

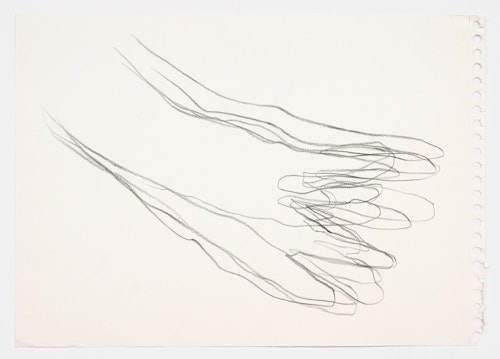

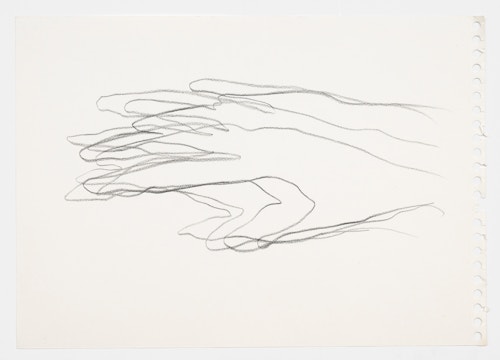

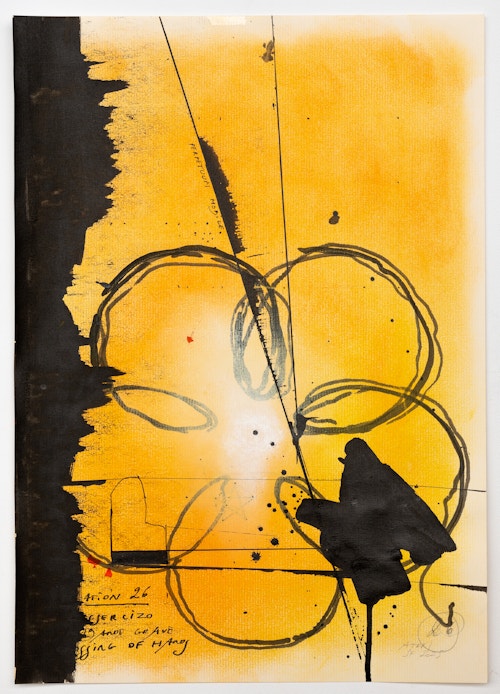

“I think of shadows. Perhaps that is where drawing began. Pliny tells the story of a young woman, in love and sorrow, tracing her lover’s shadow by candlelight as he prepares to leave. Her hand follows the contours of what he leaves behind—a fleeting trace on the wall. She moves along those lines as if each stroke of the pencil holds on to a presence that is slipping away, drawing someone she will never see again. In that gesture lies both desire and attention—a fragile balance between being and not being".

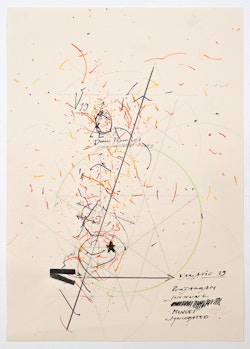

What unfolds is a field of resonances, echoing a lineage from Aby Warburg to Walter Benjamin: a mode of thinking in associations and constellations. Juxtaposing images becomes a form of listening—a way of lingering in that fragile space where meaning briefly illuminates before fading again.

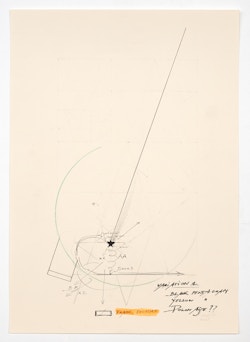

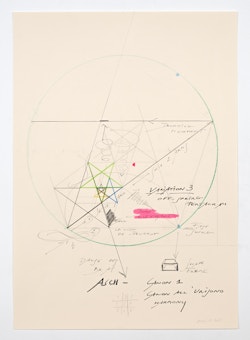

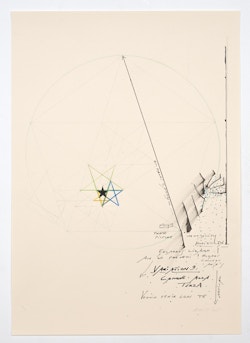

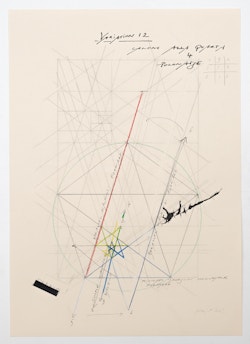

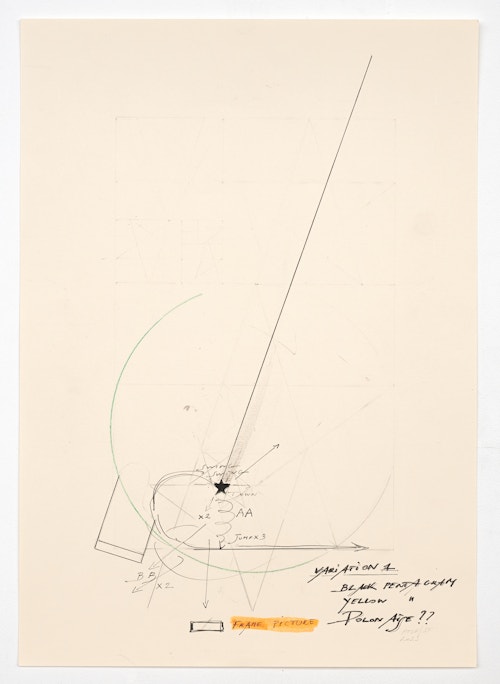

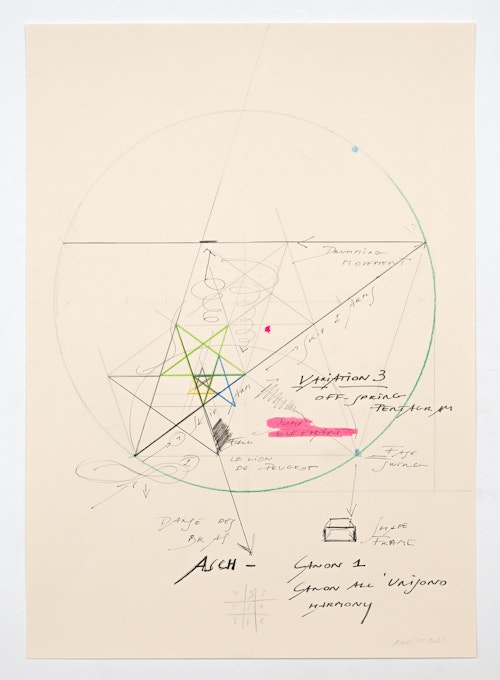

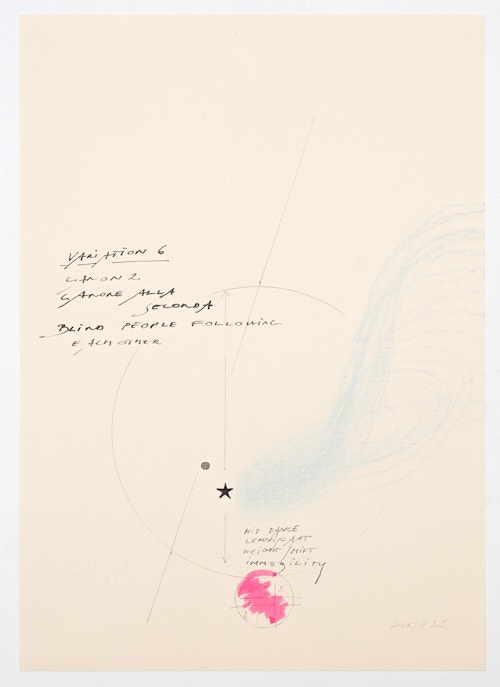

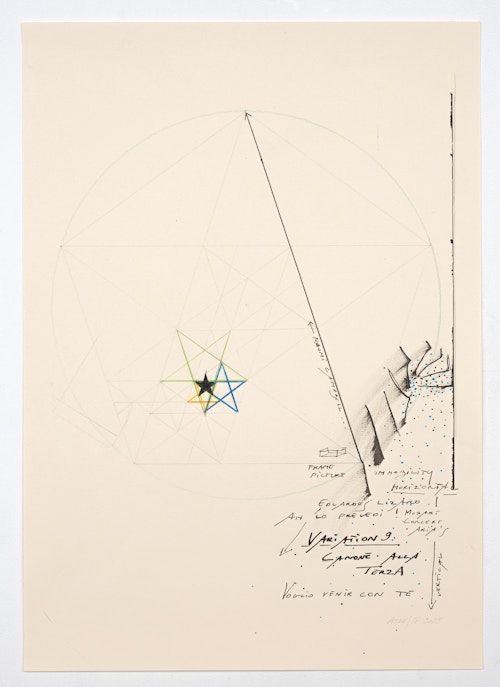

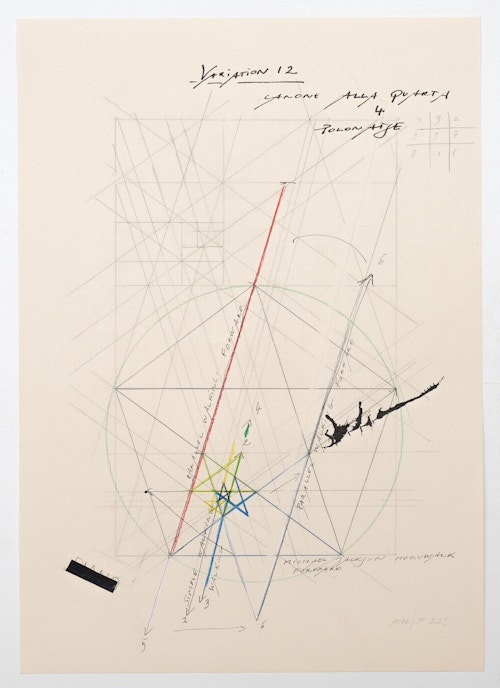

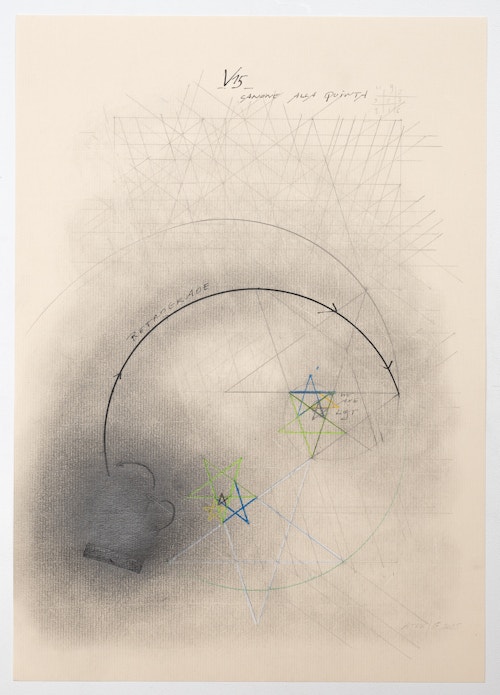

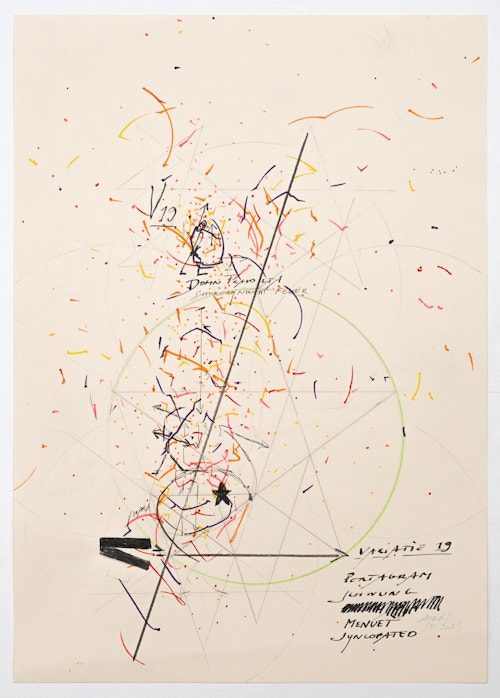

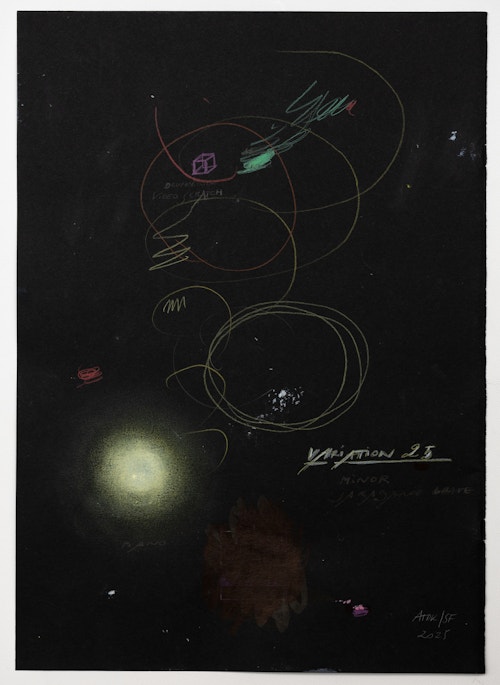

This approach aligns closely with De Keersmaeker’s own thinking. Some time ago, she showed me two images: one of her vegetable garden, geometry born of necessity; the other, a drawing that mirrors the very same figures. In that pairing, something essential surfaced. Her thinking moves in spirals—circling from the structure of a leaf to a musical interval, or from the rhythm of walking to the architecture of dance. One thought yields to the next: a restless current of connections, in which understanding follows what appears—carried along, unnecessary to name or explain.

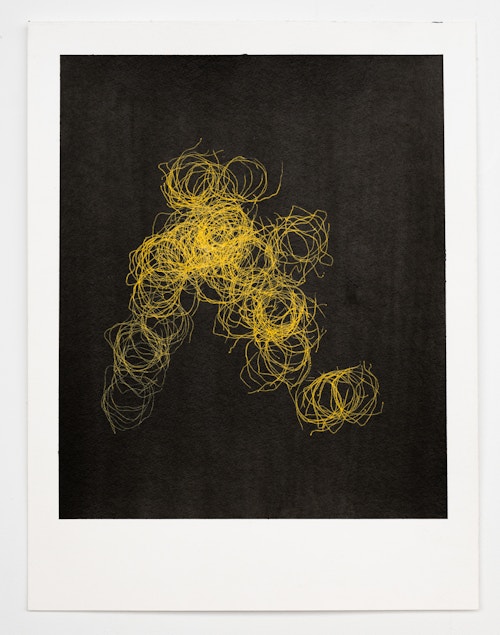

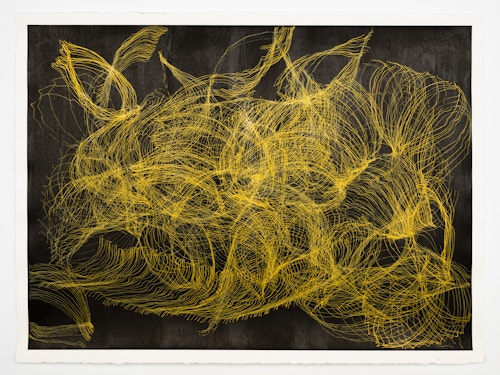

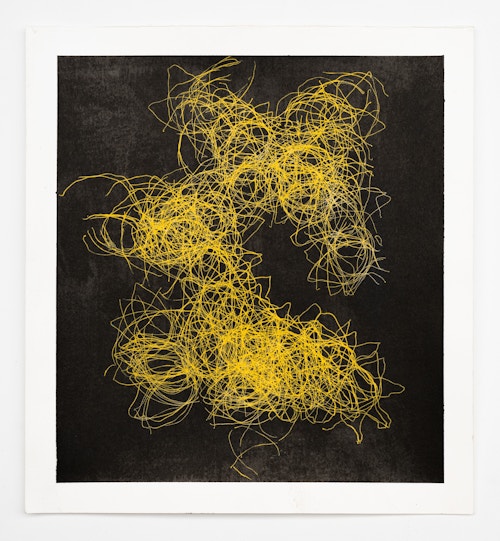

De Keersmaeker first created her Goldberg Variations with a classical, frontal setup, placing the audience directly opposite the work. When presented in the Medina of Tunis in 2023, the piece underwent a profound shift. Performed outdoors and surrounded by spectators, a new relationship emerged—more intimate, immediate, and fluid. “The circle is a democratic form par excellence, because every spectator has the same proximity and access to the event.” A living experience that repeats itself here, in the performance created for Xavier Hufkens, flowing through the architecture of Robbrecht and Daem, shaped by the spaces, responsive to their scale and entangled with the paintings and the public. That turn toward proximity carries through into the drawings. They draw the viewer in, toward the point where looking almost becomes touching.

Naked, or nearly so, her body is wrapped in a thin sheet of gold foil. Against a black void, she moves to a fragment of The Goldberg Variations, BWV 988; the body folds open and closed. The camera stays still—a single fixed frame that simply records. This steady, unblinking gaze recalls the early Portapak years: the raw, solitary experiments of Bruce Nauman or Lili Dujourie, who turned the camera into a mirror, a witness to the bare intimacy of body and studio. The movement is small, instinctive—like a child folding herself into a blanket. Egon Schiele’s Girl Wrapped in a Blanket (1911) comes to mind: knees drawn up, the blanket loosely gathered, pale, translucent skin touched by sudden glints of color—a cheek, a knee, a shoulder.

This act of envelopment—in the fragile cocoons of Marisa Merz, the textile bodies of Annette Messager, the earthy veils of Ana Mendieta, or the felt blankets of Joseph Beuys—speaks to a shared meditation on protection, transformation, and connection. Each gesture navigates the tension between inside and outside, visible and hidden, self and surroundings. It is the wrapping of a newborn, the shroud of the deceased, the ritual of sacrifice. A threshold, marking transitions between states, between body and world.

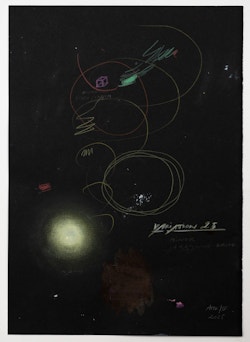

De Keersmaeker’s film is both simple and celestial. It folds the body back into itself as a source of energy, while reflecting the light that enters from the window. For a moment, the human brushes the cosmic. The dance becomes a flicker in the universe—a movement between earth and sun, between the vulnerable human body and a vast, almost unimaginable cosmos.

Its formal echo in the works that follow, also studies of light and movement—now in ink, oil and pencil on paper and panel—creates a momentum, allowing the eye to discover a gentle companionship between the works, across time and medium.

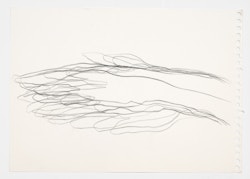

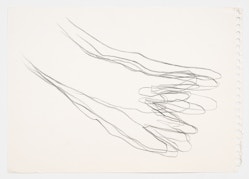

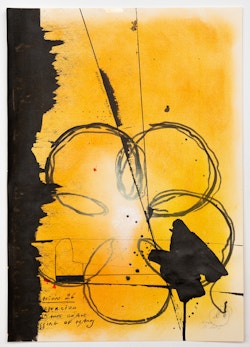

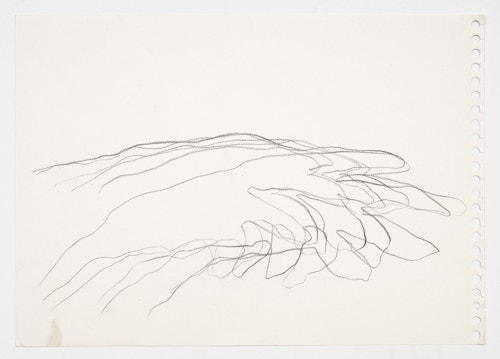

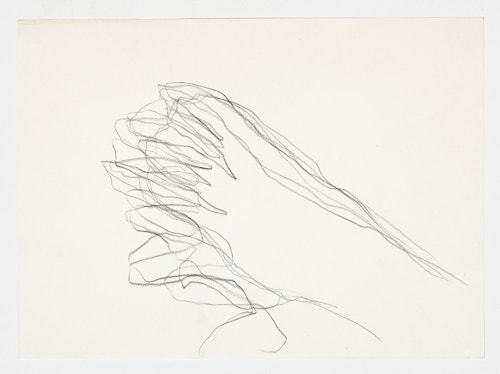

In the first work, a leaf makes its way across paper. Not outdoors, where wind might seize it, but indoors where it is gently nudged, guided, urged forward by a pencil. What remains is a faint aftermath: a wake of lines, light, tentative, almost etched, as though time itself had brushed past and left a mark. The paper becomes a surface on which time settles, gradually, layer by layer – an image that dwells on its own making.

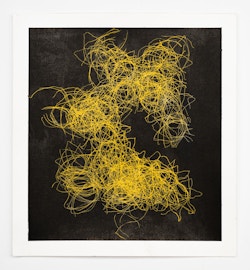

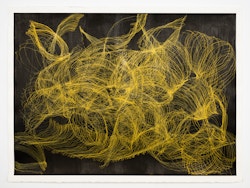

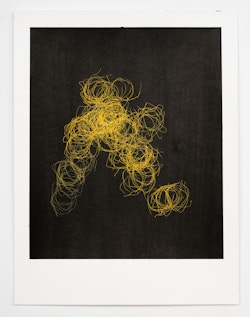

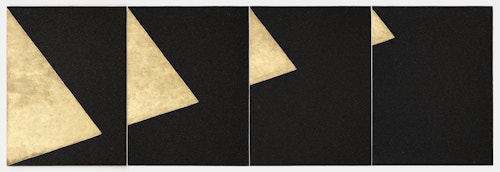

The second work is placed on the floor: four elements arranged, displaced, recombined, creating a dynamic field of form and meaning. The use of gold paint on black roofing, a recurrent material in Fillet’s work, echoes the preceding film. Here, time appears through a shrinking patch of light that forms a golden triangle, a shape poised between representation and abstraction. Gold, historically tied to the immaterial, here meets the dense industrial darkness of roofing—an interplay of weight and luminosity, matter and image that runs throughout Fillet’s practice.

The installation asks something of the body. You bend. You lean. You step closer. Gravity makes itself felt. The pull toward the floor is unmistakable—striking, especially in relation to the work of Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. Concrete yet open, modular yet ephemeral, the work becomes a choreography in which the viewer becomes a user who can actively participate.

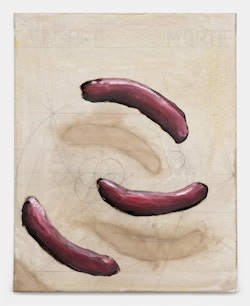

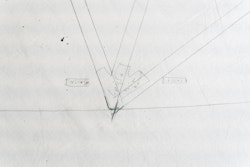

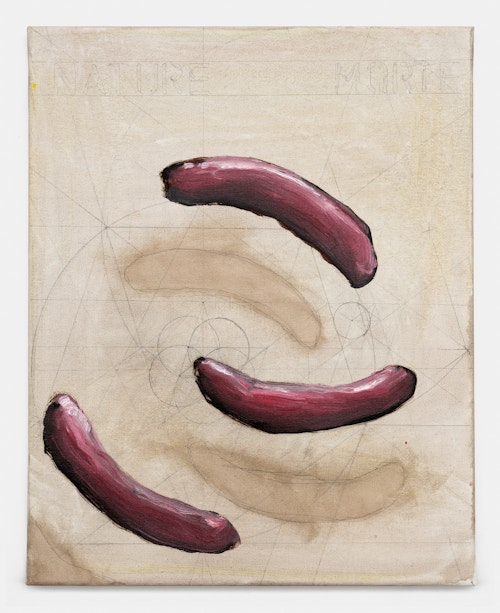

This online exhibition concludes with a recent work that condenses much of what precedes it. Three figures, floating in a seemingly casual suspension, cast their shadows onto a geometric drawing. Their presence echoes the folk song “Kraut und Rüben haben mich vertrieben, hat meine Mutter Fleisch gemacht, war ich geblieben…” (“Cabbage and turnips drove me away; if my mother had cooked meat, I would have stayed…”) that is associated with the Goldberg Variations’ Quodlibet. Like the underlying pentagram—traditionally the number of man (five fingers, five toes, five senses)—the figures evoke the carnal, the earthly, the nurturing, the material, even as their weightlessness paradoxically suggests otherwise: a contrary, quasi-immaterial pull. On the canvas, these elements weave together, just like Bach tossing a folk melody in the Quodlibet, giving a sense of the Bach household where music was a constant, every-present fact of life. Here, it comes back as a reminder that art is never separate from the life in which it is rooted.

Lieze Eneman, 2025